Reverend Dr. Samuel Hart

Reverend Doctor Samuel Hart is a fifth generation descendant of Reverend William Hart, one of the early Pastors of the First Church of Christ in Old Saybrook. He is fourth generation descendant of General William Hart. He was an esteemed man of religion and teaching and much respected throughout the Episcopal world. He is buried among the Hart Family in the front right (northeast) corner of the “Ancient Burial Ground”. Along with his traditional tombstone is a red sandstone cross which celebrates his years of service to St. Lukes Church in Middletown. The photo at left shows his headstone on the right, and his footstone to the left of the cross. His brother Dr. George Hart’s footstone is to the right of the cross. The following is a description of his life, presented by “Project Canterbury”:

Reverend Doctor Samuel Hart is a fifth generation descendant of Reverend William Hart, one of the early Pastors of the First Church of Christ in Old Saybrook. He is fourth generation descendant of General William Hart. He was an esteemed man of religion and teaching and much respected throughout the Episcopal world. He is buried among the Hart Family in the front right (northeast) corner of the “Ancient Burial Ground”. Along with his traditional tombstone is a red sandstone cross which celebrates his years of service to St. Lukes Church in Middletown. The photo at left shows his headstone on the right, and his footstone to the left of the cross. His brother Dr. George Hart’s footstone is to the right of the cross. The following is a description of his life, presented by “Project Canterbury”:

From Project Cantebury, Samuel Hart, Priest and Doctor, by Melville K. Bailey, Hartford, CT: Church Missions Publishing, 1922

The life of Dr. Samuel Hart was so manifold that a short sketch can only record impressions of one loved as he was revered. Those who knew him will fill in the sketch with such memories as never go into words. To those who did not know him it is hoped that these lines will convey at least a partial knowledge of one who, with great contemporaries, exercised in his time a real influence on the life of the American Church. To students who received instruction in the many subjects which he taught he was, and to students who would know how he helped those pupils he may be a shining example of the text, “The priest’s lips should keep knowledge.”

Heredity and environment receive their due in nearly all biographies. The power of self determination is perhaps less frequently estimated at its true worth. Anglican reserve sometimes suggests rather than expresses the greatest force there can be in any human life: the supernatural power of Divine Grace, received in Holy Baptism, supplemented in Confirmation, specialized for the priest in Ordination, and sustained in all believers by continuance in the Means of Grace. Any sketch of Dr. Hart which neglected the last would omit the chief element of his life.

The details of his ancestry are interesting, but here there is only space to say that the first colonist, Stephen Hart, was a man of adventurous courage, John Hart of Yale a brilliant scholar, “Priest Hart,” the Congregational minister of Saybrook, a strong and conservative character, and Judge Henry Hart, Dr. Hart’s father, a man of great power in body and mind, and universally respected.

Not less influential was the ancestry of his mother, Mary Ann Witter. On the maternal side there was a gaiety, and a touch of mental genius, which half account for the hereditary traits of her son. Her great vitality sustained her to the age of more than ninety-eight years.

Having received his preparation in the Rev. Peter L. Shepard’s School of Old Saybrook, and at Cheshire, at the age of seventeen he entered Trinity College in 1862, after the dashing young Southerners had left to join the ranks of the Confederacy. He came to the old, ivy-covered, brownstone buildings, southeast of the site of the Capitol, and to the gardens which lay west toward Park River. Though Hartford had as yet only Bushnell Park, it was a beautiful city. Despite the gloom of war, it was the city of which Edward Everett Hale declared that there is more of real life to be found in such than in any other kind of a community. Mrs. Colt, to whom the young student was second cousin, was queen of Hartford society. Authors of international fame dignified it with letters. Its pulpits were occupied by eloquent preachers. And the College Faculty was composed of men able to inspire true love of learning.

Having received his preparation in the Rev. Peter L. Shepard’s School of Old Saybrook, and at Cheshire, at the age of seventeen he entered Trinity College in 1862, after the dashing young Southerners had left to join the ranks of the Confederacy. He came to the old, ivy-covered, brownstone buildings, southeast of the site of the Capitol, and to the gardens which lay west toward Park River. Though Hartford had as yet only Bushnell Park, it was a beautiful city. Despite the gloom of war, it was the city of which Edward Everett Hale declared that there is more of real life to be found in such than in any other kind of a community. Mrs. Colt, to whom the young student was second cousin, was queen of Hartford society. Authors of international fame dignified it with letters. Its pulpits were occupied by eloquent preachers. And the College Faculty was composed of men able to inspire true love of learning.

He must have been a rather serious young man, the youthful presentation of the young clergyman described later in the “Hartford Courant”:

“He was a handsome man, dark-eyed, somewhat slender, with dark hair. . . . In after years he became eminent in the Church, revealing as he grew older and of wider experience, the innate quality of humor which in those younger days he carefully repressed.”

It was not always repressed. The Rev. Dr. Frederick W. Harriman remembers that he called to young Hart on the campus in examination time, “How are you feeling?” and received the quick reply, “Like Sisyphus!”

His classmate, Mr. B. Howard Griswold, writes that “He was a hard student and, while not especially identified with the games or other activities, physical, social, or musical, of college life, he was by no means a recluse, and was frequently a guest at entertainments of the hospitable families of Hartford.” Mr. Griswold also speaks of the affection in which he was held by his fellow students, the greatest pleasure being evinced by all when he had gained the distinction of “Optimus,” having exceeded the highest marks of any student of previous years.

President Luther said in the College Chapel:

“Officially I would say that when he was graduated from college the books of the registrar showed his marks to be the highest ever received in Trinity College, and unofficially I would say that those marks have never been equalled by any Trinity student. He was almost perfect in all of his studies.”

Student at Berkeley

The next epoch in his life came a good deal like a dissolving view, where one picture begins to show before the other has disappeared.

He entered the Berkeley Divinity School in 1866, coming fully under the influence of one of the greatest men the Church or the Nation has ever had, Bishop John Williams, a man in the same class as Washington nothing less.

He had not finished at the Berkeley, however, before he was called back to Trinity, to begin that course of instruction in many branches which lasted thirty years.

Hart as a Young Teacher

Under this caption the Rev. Dr. Lucius Waterman, the second Optimus of Trinity, writes:

“I entered Trinity College in 1867. I think it was not until 1868 . . . that our Professor of Mathematics fell ill, and Mr. Samuel Hart came to take his place. From that time on there was a succession of disabilities of teachers in one department and another, and always it was Mr. Hart who came to fill the breach. . . . And what a teacher he was! I think he worked his classes harder than any other member of the Faculty. I am sure he taught them more. Some of the other men of the Faculty taught me much, and did some things for me that were greater than teaching. But none of them equalled Mr. Hart in photographing his ideas on the sensitive plate of a student’s mind, and making a clear and indelible picture there.” “His clearness and power of impressive impartation” were ever characteristic.

In 1869 he was ordained Deacon, and another writer says, “The Rev. John T. Huntington, then Professor of Greek, had a quick eye and a warm heart. He had seen the brilliant promise of this young scholar, and had a vision of what it might mean to the College to secure him as one of its Faculty. So Professor Huntington discovered that he was in need of rest, and offered to assign a large part of his salary to the maintenance of a tutor in Greek, if the trustees would appoint Mr. Hart to such a position. The young tutor made himself soon an indispensable part of the College life. The position of Secretary of the Faculty gravitated to him by natural process, so accurate was he, and so neat, and so beautifully fair were the records that he kept in that graceful chirography of his. From 1870 to 1873 he was assistant professor of mathematics, and full professor from 1873 to 1883, enjoying a brief leave of absence, with care of the American Church in Paris, in 1878-9. He was Professor of Latin, 1883-1899, for there was nothing he could not teach and teach masterfully, if he gave his mind to it, and really he seemed to give his mind to most things.”

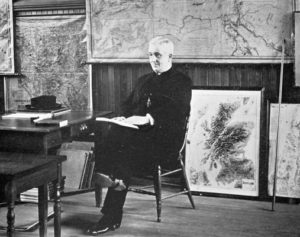

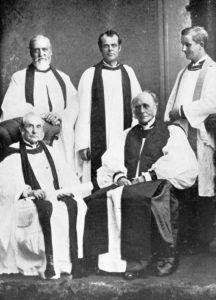

There are two photographs which show very well his personal appearance in that bright period of college teaching from 1869 to 1899.

The first, in the group of delegates to Scotland in 1886, indicates the slightness of figure so characteristic of his younger days, while the second, as Professor of Latin, shows remarkably well his extraordinarily polished appearance. In the photo, Reverend Hart is on the right.

The writer of these lines recalls his first impression as one of those experiences which make life good to live, indelible as memory itself, and in the supreme order of human existence.

On a hot September day in 1875 a group of young men sat in a class room in Trinity College waiting for their entrance examinations. Their situation was the essence of discomfort, physical and mental. Presently there stepped quickly into the room a slight youth whom they took for a Junior, possibly a Senior.

To their astonishment he said, “I am Professor Hart.” He then distributed the papers, with some cheering words, and saying with a laugh, “You will find plenty of ice water in the pitcher on the stove,” left them to their work. That brief appearance changed the situation, absolutely. Gloom was converted into cheerfulness. They applied themselves to their task with alacrity, and the prospect of entering Trinity became more fascinating than ever. His appearance in the class room was incredibly unexpected. He taught mathematics then. Mathematics demands chalk, chalk leaves dust, and the dust is white. But Professor Hart was immaculate and shining neatness from top to toe. His hair was dark with a rich natural gloss, and full. His eyes were dark and very bright, and he was often smiling. He invariably wore a suit of doeskin, the handsomest of the black cloths, having a bright, satin finish. His shoes, unlike those of which he used gaily to quote,

“And always on Commencement Day

The tutors blacked their shoes,” every day shone like ebon mirrors. His collars, ties, cuffs, were always fresh and snow white. It is not possible for any man to be more immaculately dressed anywhere than Professor Hart always was in his dusty class room.

It is no wonder that this young Professor, to whom knowledge was native and its rendition joy, whose personal appearance seemed to say, “The dew of thy birth is of the womb of the morning,” and to whom living appeared a delight,–it is no wonder that he was idolized. Professor Hart seldom had to call his class to order. He kept his students so busy they had no time to think of mischief.

Varied Learning

Dr. Hart’s wide knowledge was always a subject of general admiration. A slight examination of some of the concrete details of that knowledge deepens our admiration.

The Latin language and literature held the first place in secular studies. That he was very fond of the language itself is well known. His Latin library was large, but by far the greater part consisted of editions of Juvenal, whose Satires he published with notes. He also published the Satires of Persius, and an edition of Scipio’s Dream. There was a college tradition that he had nearly completed an annotated edition of Tacitus, when Professor Holbrooke’s monumental work appeared. In his library were rare and beautiful editions of Virgil, Horace, and other authors. He knew the colloquial Latin of Plautus and Terence, and that of inscriptions, literary and otherwise, and there is no doubt of his acquaintance with the monkish Latin of the Middle Ages. In conferring degrees, although the forms were short, he manifested graceful facility in the oral use of the classic tongue. In his later years, at least, he corresponded in Latin with Bishop Doane of Albany.

Dr. Hart’s knowledge of Greek must have been quite extraordinary. He edited no author in that language, but was chosen to write on one occasion a letter in Greek from the American Church to the East, and wrote at least one Greek hymn. His books included not only the classics, but various editions of the Septuagint, the Greek Fathers, and the Liturgies with comment, as later noted. Without question he read the New Testament Lessons in Greek every day.

In 1875, when Professor Hart was thirty years of age, a Boston newspaper printed the statement that he was corresponding in French with a learned professor in Paris. It is not ascertainable if that were true, but it is certain that he read it with ease, and understood it when spoken. There is no evidence that he gave much attention to German, Italian, or Spanish.

Mathematics was not Dr. Hart’s preference, but he went far in that field, lecturing and teaching at Trinity College in all branches, from addition to calculus, with an exploration into the fourth dimension, which, he said, proved that an orange could be turned inside out without breaking the skin.

To a considerable extent he knew applied mathematics, as in surveying, which he taught, including the use of the theodolite. He taught navigation also, and told the story of a passenger who, when the officers were disabled, brought the ship safely to port by the application of his college studies. We all believed that Professor Hart could have navigated a ship through all the Seven Seas.

Physical science seems almost as remote from philology as does mathematics, yet Professor Hart knew and practised it. The Rev. Dr. Lucius Waterman writes of a friend, “He came back to College one Summer, when Mr. Hart had been teaching natural science, and Mr. Hart mentioned with satisfaction that ‘we have performed successfully every experiment but one in Ganot’s Physics’.” For years he was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Professor Hart brought to his department of astronomy a knowledge of chemistry and physics, coupled with mathematics, which, inspired by a vivid imagination, made his instruction extremely interesting and intelligible.

The illustration which he used at the old Trinity College to express the relative sizes, and distances, of heavenly bodies is too graphic to be omitted:

Sun–sphere 56 in. diam. at old State House.

Mercury–small currant–Cor. Central Row.

Venus–rather small cherry–old Post Office.

Earth–cherry–Universalist M. H.

Mars–cranberry–Athenaeum.

Asteroids.

Jupiter–moderate sized melon–C. O. Ave.

Saturn–rather smaller–below Mrs. Colt’s–one mile from sun.

Uranus–peach–one mile below.

Neptune–little larger–one mile below.

Nearest star–40,000 miles.

No one could quite forget astronomy taught with a merry laugh in terms of the garden, orchard, and Hartford streets.

One notable day in his course in astronomy was that of a transit of Venus. He brought the small college telescope out on the campus, and let everyone see through it an intensely black little spot dancing across the fiery circle of the sun. And it was like him to see that no one looked so long as to rob the others of the view.

The Professor of Astronomy was also a practical meteorologist. He understood the meaning of common phenomena which everyone knows but no one understands, how fog differs from cloud, why the cobwebs show on a cloudy morning when the sun will come out later, and whether sound does or does not come more slowly against the wind. He kept a daily record of the rainfall. One night a while before midnight he and Professor Brocklesley went out on the campus to set the sundial by the North Star. They observed the extreme east and west positions of that supposedly unchanging star, and set the gnome exactly between. Every day’s exact sun time was posted in the reading room in the clear handwriting we knew so well.

These were the subjects of which we thought most, though we would have agreed with a fellow professor at Trinity who expressed his belief that Professor Hart could teach any branch in the curriculum at half a day’s notice.

Notes of his knowledge of sacred learning will come more properly under his work at the Berkeley.

With the Newspapers

Dr. Hart was always on good terms with newspaper men. They spoke of him with an affectionate admiration rarely evoked in that contact of theirs with every side of life, which is in fact wider and more universal than that of any other profession. His writings for the press, if collected, would far exceed his writings in book form. This work of his began while he was yet a college student.

In the anniversary edition of the Hartford “Courant” in October, 1914, he wrote:

“I have been for fifty years a voluntary and irregular contributor to ‘The Courant.’ I have presented many a news item or report, many an obituary notice, not infrequently a historical review or other article, occasionally a criticism or correction. . . . Perhaps [at first] I began to act or look as one who wished to fill up a large space in the columns; for the first time that General Hawley spoke to me, as far as I remember, was when he stopped at the chair where I was writing, and said, ‘Draw it mild!’

“As to items of news, academic and ecclesiastical and historical, accounts of large events like conventions and centenaries, and notes of minor and minute matters, I have contributed my share towards attracting the attention of the readers of ‘The Courant’ in advance and informing them afterwards of what has been said and done. At times I have written extended notices of historical and other publications, having the strong desire in these, as in my own lectures and addresses, to bring the past before the minds of readers and listeners at the present day, to honor the characters and the deeds of the worthy men of old, to quicken the sense of our obligation to their goodness and bravery, and to learn the lessons they teach us as to our duties and the way in which we ought to meet them.”

The impression he made at the newspaper office, after the student days, in his early ministry, has been quoted to illustrate also his class room. That impression deepened into warm personal friendship as the years went on. His friends in the editorial sanctum enjoyed telling personal stories about him. Here is one:

“He ate his meals in a house across the street [from the old college]. Three or four students also went there for their meals. One day the boys rashly attempted some mystification aimed in his direction, and the dignified professor who they believed knew everything worth knowing, replied promptly, calmly, and efficiently, ‘Young gentlemen, the faculty are not so green as they look’.”

Another wrote, “Dr. Hart knew how to anticipate an event with the nicety of a trained reporter. It is little wonder that his copy was hailed with delight by those who handled it in a newspaper office.”

And another wrote, “Dr. Hart was always on the lookout for the press tables at conventions, and never a speaker arose to address the chair or to debate an issue but that Dr. Hart supplied his name. He was never too busy, even with his multifarious duties, to answer questions of the newspaper men–and they appreciated it.”

On the occasion when the Delaware clergy voted for Dr. Hart as bishop–a vote not sustained by the laity–the “Courant” under the heading, “We keep Dr. Hart,” said, “This isn’t the first time a bishopless diocese has tried to take away Dr. Hart from us, and we’d like it stopped. He belongs in Connecticut. He’s wanted for home consumption, as Hosea Biglow put it.”

He was for many years the accredited American correspondent of the London “Guardian,” the greatest of the English Church newspapers, to which also he contributed letters. On the occasion of. a controversy, in which it would seem Dr. Hart had written, one contributor exclaimed of another, “Mr. doesn’t know everything! Dr. Hart is a very different kind of a man.”

Dr. Hart laughed at the unintended intimation that he did know everything, but after all that was the general impression his friends had of him. It was the “Guardian” that described him as “a capital Churchman,” a characterization, it was observed, that might be added to High, Low, and Broad.

Yet of the representative of this stately Anglican churchmanship an American writes:

“One newspaperman will never forget how Dr. Hart, placing both hands on his shoulder, looked earnestly into his face and in a low voice asked him about his soul’s welfare. He had never thought of the doctor as a large man before, but with him standing so close, and inquiring so searchingly and so seriously, it seemed a long way for an instant as he raised his eyes and looked into that face that was bending over him with so longing an intent. The contact of that moment, and the lowly-spoken word, was so intimate and steady and friendly that it made a lasting impression.”

After his death the “Hartford Times,” and the “Hartford Courant” had extended and appreciative reviews of his life and work, and many other periodicals had articles, from brief notices to complete summaries of his personal history.

His Love of College Boys

To return to his professorship at Trinity,–for thirty years this priest of the Church, whose outward life was a daily obedience to the Ten Commandments, and a fulfilment of the Beatitudes, and whose inward life, we may reverently surmise, was the sacramental life sustained by Divine Grace, held his place as the teacher of young men whose characters varied as those of all college students do, and apparently won the confidence and affection of every student in the college in his day.

Students always nick-name their teachers, from tutor to president. J. G. Holland protested against nick-names as a degradation of human nature, but Horace Bushnell argued that the character of a word lies in its content. “Sammy Hart” among the students, and “Sam Hart” with his fellows, carried no shade of meaning discordant with his splendid intellect and consecrated faith. It denoted affection. Yet he was a disciplinarian.

A few incidents and records avail to indicate the reaction of many students to their teacher. Dr. Waterman writes: “A distinguished gentleman told me not long since how Dr. Hart discovered him and a future bishop matching pennies during a recitation hour, and his language was painfully severe’.”

The boys could not help having a little fun with him sometimes. These incidents will seem very slight to a stranger, but to his old students they may call back many a scene not soon forgotten.

In mathematics he carried a string, to make circles. When not in use he held it tightly drawn behind his back. One day a student cut it with a pair of scissors. Professor Hart, his hands suddenly released, went right on talking without a sign, save a slight gleam in his eyes, and a richer humor in his voice.

His handwriting seemed inimitable, but one morning there appeared on the bulletin board in his unmistakable script, and signed with his name,

“Students will please take notice that John Morrisey’s son died of smoking cigarettes.” Half the college was fooled before the imitation was discovered.

The door of Professor Hart’s own room was the only one in college which was never locked, and it was never known to have been entered, save one Christmas vacation when two undergraduates whose names are now known to all Trinity alumni, walked in, and left unmistakable signs of their invasion, unable to resist the temptation.

One night before Commencement three students were letting off their spirits in a run and tumble down the stairs, when a really sharp voice, “Why, what’s the meaning of this?” revealed the Professor. Choking with embarrassment they stammered, “We’re celebrating the last day.” “The last day!” he replied instantly, “why, the end of the world hasn’t come yet.”

Another summer night two students in the same mood were making a really awful racket in their room, when there was a knock at the door. “Come in!” He came in, and to the men whose faces were almost blanched, he said, “You don’t call this ‘Paradise Section,’ do you?”

Some old verses about the faculty in those days contain this:

“Next in line in Samuel Hart,

In every branch exceedingly smart.

He tips his hat politely–so–

And lives ‘Pro bono publico’.”

Dr. Slattery has written: “Long before I ever met Dr. Hart I heard of him from students of Trinity College, Hartford. He taught Latin there, and won the respect and affection of all the men. . . . One of them told me that when at Chapel they read in the Psalter, ‘He maketh my feet like hart’s feet,’ they always turned and looked at Professor Hart.”

He was not unobservant of little points himself, and was immensely tickled by one dignified member of the Faculty, who, he declared, always announced one hymn, as “O come, Loud Anthems, let us sing.”

He also said that that friend pronounced a word in the second collect like the capital city of New Hampshire, and said he didn’t see why the Lord should love Concord more than any other town.

He said, too, that the same friend, when some one else read the Litany, pronounced every response with a different inflection.

Such comments on some lips would be dangerous, but with Professor Hart it was only the rippling humor with which he illumined the friends he loved, and in it there was no sting and no irreverence. And it was noticeable that he never referred to anyone’s manner of celebrating the Holy Communion.

It might be thought that one who saw absurdities, inconsistencies, and errors so clearly, and whose ready wit was so like a two-edged sword, would have been feared by his students. It was not so. That was the wonder of it. The greenest freshman who ever deepened the color of he college campus never felt that he was the object of ridicule to Professor Hart. And on the other hand there was never a boy so wild but that he trusted “Sammy,” realizing that his teacher’s purpose made for his felicity.

As an undergraduate he had been initiated into Beta Beta, and when that affiliated with Psi Upsilon went with it. His old Fraternity, now the Trinity Chapter, honoured him as one of its most distinguished members.

At the time of his death Professor McCook drew up resolutions for the active chapter of the Connecticut beta of the Phi Beta Kappa, doing honor to Dean Hart, as former secretary, vice-president, and senator for life of the national fraternity, whose honorary membership, it has been said, is the highest scholastic honor in America.

The “1918 Ivy,” dedicated to the memory of Dr. Hart, quoted from Tom Brown’s visit to Rugby, ending:

“If he could only have seen the doctor again for one five minutes–have told him all that was in his heart. What he owed to him, how he loved and reverenced him, and would by God’s help follow his steps in life and death–he could have borne it all without a murmur.’

“What Arnold was to Tom Brown and Rugby, Doctor Hart was to hundreds of men and to Trinity College.”

College Chapel Sermons

Dr. Hart’s written sermons show minute analysis, with a logical catena binding the members into a strong integrity. His English was notable for its even polish, and selective use of words, and their discriminating pronunciation.

Dr. Waterman records that “his sermons began to be a great power in my life. I recall vividly–the one in which he brought together the parables of the Pounds and the Talents–or the one about the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart–that sermon where the young preacher spoke of men who think that ‘falsehood in College is not lying, and stealing in College is not dishonesty’.” He speaks of ‘an Advent Sermon, for Bishop Williams, on Eternal Punishment.

Others remember a sermon after a college outbreak from the text, “Brethren, be not children in understanding; howbeit in malice be ye children, but in understanding be men,” That sermon penetrated the understanding of those who heard it, as did the one in which he warned the students that they could not insert parentheses of wrongdoing into an orderly life,–“in life there are no parentheses.”

There was indeed a note of sternness in some of those college chapel sermons, which suggests a rocklike basis of character underlying the qualities of which Dr. Geo. Francis Nelson quotes,

“Though round its breast the rolling clouds are spread,

Eternal sunshine settles on its head.”

Travels Abroad

In 1878-9 Professor Hart took his first sabbatical year. Three volumes of letters to his family and a great folio volume of photographs contain a graphic record of his travels in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and of his sojourn in Paris, where he was in charge of the American Church from New Year’s to March, 1879. Footloose and alone as he was, he travelled, save at Paris, when and as he would. He went to the British Isles well equipped with knowledge of our ancestral history, and his future work in liturgies may well have been richer for his concrete knowledge of the historic background, and of contemporary British life.

When he landed in France, the customs officer seemed chiefly concerned with “tabac.” “I told him, Je ne fume jamais,’ which seemed to satisfy him.” To the truth of which his American friends could testify!

Professor Hart found Paris extremely interesting, and wrote with vivid enthusiasm of its places and pictures.

He enjoyed his service in the Church greatly, with large congregations, and fine philanthropic work, and he met many people, mostly English and American. He met Père Hyacinthe also, heard him preach, and translated an article of his for “The Churchman.”

“Yesterday,” he wrote, “I went to the National Library, which has only 1,700,000 books–they would be glad of your extra Congressional Globes.”

He writes of Da Vinci’s “Marriage at Cana,” and asks, “Do you know that Da Vinci invented the wheel-barrow?”

Again: “I had a letter yesterday from Cotton at Dresden, and he wants me to go to Italy with him; but I cannot do it without missing part of England, and I rather think I will leave that until another time. It isn’t easy to tell how far anything is or how much it weighs, or how cold it is here; for all the measures are different from ours.”

The classroom work was interrupted again in 1886 when, with Bishop Williams, Dr. Beardsley, Rev. Samuel F. Jarvis and Rev. Wm. F. Nichols, he was elected delegate to the Scottish Church on the occasion of the Seabury Centennial. Their travels had much variety. Dr. Hart writes of one evening,

“At half past seven we went to dine with Dr. Hatch (the head of St. Mary Hall), Dr. Driver who is Dr. Pusey’s successor in the Hebrew Chair, and Prof. Sayce the great Assyriologist, besides Dr. Hatch’s sons.”

Professor Hart traveled with his American eyes wide open even in beloved and reverenced England, and he and his friends must have had some amusing experiences like the one hinted at in a letter from Bishop Doane long after, in 1912, referring to some excursion, where he asks:

“I wonder if you will be willing to add to your kindness by sending me a copy of the verses which I wrote. I am writing a sort of story of my life, trying to make it interesting and amusing, and this sort of thing helps very much.”

The lines, which are indeed amusing, making rhymes with wildly Gaelic Scottish names, at the end crescendo into classic Latin:

“Till, soaked through and slightly coolish,

We arrived at Ballachulish,

But as Virgil’s hero habet,

‘Meminisse haec juvabit’.”

The delegates brought back a trophy in the form of a pastoral staff presented by the Scottish Church to the Diocese of Connecticut.

Esteem of His Fellow Teachers

The estimate of his college work by his fellow teachers may be accepted as impartial and accurate. Dr. McCook speaks thus:

“He had an active, acute, discriminating, constructive, a remarkable brain. . . . He had a prodigious memory, but he was also remarkably industrious and systematic. Besides the branches of science which he had mastered sufficiently to teach, he found time to attend to the duties of librarian, which he did with his usual thoroughness and efficiency. He also kept in touch with the incidents of the students’ personal life. He mothered the sick, gave the useful touch here and there to push forward or hold back in the presence of temptation. He preached often in the chapel, and was for a considerable time the soul of the missionary society. He was secretary of the Phi Beta Kappa, doing his utmost to make it a power for the stimulation of high scholarship.”

The President of Trinity College, the Rev. Flavel S. Luther, Professor John J. McCook, and Professor Robert B. Riggs, drew up a series of resolutions in which they spoke of his profound scholarship, singular gifts as a teacher, his unswerving loyalty to his Alma Mater, his manifold service in the larger field outside the college world, his lofty ideals, and his unblemished Christian character.

Formal tributes often seem cold, yet those to Dr. Hart contain all that is implied in this incident:

On a Good Friday when the Rev. J. O. S. Huntington, O. H. C., was giving the Three Hours’ Service in the Church of the Transfiguration, New York, he quoted a poem which so impressed his hearers that a number came up to speak to him about it, among them Dr. Hart’s sister. Fr. Huntington offered to write the lines for her on a card, and she then introduced herself. Fr. Huntington stopped talking entirely, looked away as if into the distance, and said quietly to himself, “Dear old Sam.” When told of it Dr. Hart said, “I had no idea James thought so much of me as that.”

Sub-Dean and Dean at the Berkeley School

The tributes from Trinity College, though spoken years afterward, have been cited above because they summed up his work there, previously to his call to the Berkeley Divinity School, in 1899.

Of this School founded, and for forty-five years conducted by Bishop John Williams, Dr. John Binney was Dean, the great and worthy successor of the Bishop. One who heard John Binney teach Hebrew felt that he spoke for the prophet Isaiah. But Dean Binney felt the need of help, and Professor Hart was called to be Sub-dean.

For nine years he held that position, teaching Doctrinal Theology, and the Prayer Book, until, on the death of Dean Binney in 1908, he was elected dean.

Less, perhaps, has been said of Dr. Hart’s knowledge of doctrinal theology than of any other branch of his learning. This was natural, because it does not come out into evidence, like the others. But he used to say, “Theology is an exact science,” and his books prove, what his pupils could doubtless testify, that he had read straight down from the beginning, in the theology out of which came the Anglican Reformation.

Dr. Hart did not stop with the Elizabethan settlement, however, for he had read down to and through the English writings of his own time.

In the course of these studies he mastered the department which is, perhaps, least studied, canon law it is needless to say not only the Constitution and Canons of this our church, but the corpus of ecclesiastical law in its rise, climax, and decline. It is probable that Dr. Hart considered his highest degree that of Doctor of Canon Law, bestowed by his alma mater, Trinity in 1899.

It is of great value to study Dr. Hart’s teaching about the Divine Liturgy of the Holy Eucharist, in his work on the Prayer Book.

He apparently takes as his foundation the whole order given in the Apologia of St. Justin Martyr, summarizing it thus:

- The memoirs of the Apostles or the writing of the Prophets are read, so long as time permits.

- The President instructs and exhorts to the imitation of these good things.

- All rise together and offer prayers.

- We salute one another with a kiss [and alms are received for the poor].

- Bread and wine mingled with water, are brought to the President.

- He taking them gives praise and glory to the Father of the Universe, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and offers prayers and thanksgiving at considerable length, according to his ability.

- The people assent, saying, “Amen.”

- They who are called deacons distribute to the congregation the elements which have been blessed–and carry a portion to those who are absent.

Dr. Hart adds: “Every full and formal celebration of the Holy Communion to this day is a service which contains the reading of New Testament Scriptures (the ‘Memoirs of the Apostles’ are probably the Gospels and the ‘Writings of the Prophets’ the Epistles), a sermon or homily, prayers, acts of charity, the presentation. of the appointed elements, the blessing of the elements by the celebrant with thanksgiving and prayer, the ‘Amen’ of the congregation, and the communion in the elements which have been consecrated.”

With this criterion in mind, probably, he had undoubtedly compared the structure of every great liturgy available with this order of St. Justin Martyr which he took as the norm. It is scarcely too much to believe that he held in mind the complete order of each, noting likenesses, differences, and variations. This was true of the principal families, the Western Syrian, and Byzantine, the Eastern Syrian, the Alexandrian or Coptic, the Greek Liturgy of St. Mark no longer in use, the Gallican, and the Roman. Naturally he knew the Ambrosian and the Mosarabic. He also knew old, odd relics of Celtic liturgies, and the liturgical forms of Nonconformists.

The forms of Liturgy in Greek and Latin he had undoubtedly studied word for word. His acquaintance with those tongues was only second, if second, to his native English, which he studied to the last punctuation mark. This is indicated by written slips left in his copy of “Tetralogia Liturgica: sive S. Chrysostomi, S. Jacobi, S. Marci Divinae Missae: Quibus accedit Ordo Mosarabicus.”

“The Divine Office,” or Orders for Daily Morning and Evening Prayer, and all other services, were studied not less carefully, and with reverence for their religious value.

As he was also an accomplished astronomer, the “Preliminary Pages of the Prayer Book” were a source of great enjoyment, and he notes that there is a slight error, which, however, “will not amount to more than one day in the three centuries 1900-2199.”

His attitude toward the Prayer Book version of the Psalter is of interest in view of his knowledge of Hebrew. That knowledge was so exact that he made sundry notes in the margin of the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon. One scarcely dares repeat that a friend said that if for a moment he forgot a phrase of the English Psalms he recalled the Hebrew, and then translated. With this knowledge he writes, “In the preparation of the present Standard of 1892, the text of the Psalter was carefully studied and corrected where errors had crept in, so that it is now far more accurate than that in the English Book and almost ideally perfect.”

If what is written above seems too technical for the devout young Churchman, it may be summed up in this:

That one of the Committee, who set forth our Prayer Book, had carefully read all the great forms of the Holy Communion known since the Church began, and gave the utmost care of which he was capable to make the American Prayer Book perfect. If we use it devoutly as he used it, we may hope to receive also a measure of the Divine Grace which he received through its use.

Hart as Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer

The effort has been made above to indicate Dr. Hart’s vast liturgical learning. His office as Custodian was a natural result, the intermediate step to which was his appointment on the Committee on Revision.

The leader of the Revision was the Rev. William R. Huntington, D. D., who made the motion in 1886. The chief purpose of Dr. Huntington was to extend the use of the Prayer Book more widely in American life, and to increase the flexibility and richness of its use in the Church which held it. It is unlikely that Dr. Hart originally felt the need of that, but having accepted the position on the Committee he co-operated with the utmost efficiency toward the ends in view.

Dr. Hart understood and held in mind the long preceding history of every office in the Prayer Book. He knew the origin and meaning of every phrase, whether in Hebrew, as in the Psalter, or Greek as in the Epistles, Gospels, and parts derived from the Greek Liturgies, or the Latin of the forms derived from the Western Church.

In consequence he had an historic criterion by which to judge every proposed change or addition, and was able to do his part in so shaping it as not to break with the past.

To his knowledge of what one is tempted to call the comparative anatomy of the various forms of the Divine Liturgy, and precise verbal acquaintance with the originals, Dr. Hart added a very exacting standard of typography, so that in so far as his influence was felt in the Revision of 1892, it made for almost microscopic perfection of the printed text.

The plates of the Standard Book of Common Prayer are folio, the pages on which they are printed measuring 10 x 14 inches. When the special edition had been printed Dr. Hart said: “We immediately began looking for mistakes.” If any were found they are not on record. The ordinary reader wonders if at its publication there had ever been any better printing. The engraving of type and borders is sharp and clear, the impression of each page uniform, the paper for each member of the committee, vellum,–of the highest quality. This printing was made possible by Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan.

The Book was printed by the De Vinne Press. The house had a staff of wonderful proofreaders, and it is believed that this volume is by the firm considered as their chef d’oeuvre.

It is said that no book has ever been printed without an error. When the Standard Book of Common Prayer was submitted to the General Convention, Dr. William R. Huntington stood, and, mentioning Dr. Hart’s name, challenged anyone to find in it a single mistake. Yet Dr. Hart said that just as they were going to press a misprint, CHRUCH, was discovered on the title page.

Hart as Secretary of the House of Bishops

Dr Hart made this position unique in the history of the American Church. Himself an ecclesiastic of episcopal dignity, who had declined the election to the Diocese of Vermont, and put aside the very singular honor of going to Japan as Bishop, he performed the duties of Secretary with a care extending to the minutest details, [23and with a distinction befitting the House which a Chief Justice of the Supreme Court at Washington has called “the most august body of men in the United States.”

The Rev. Geo. Francis Nelson, S. T. D., Assistant Secretary, throughout Dr. Hart’s term of service, and his successor, writes:

“When the General Convention of 1892 met at Baltimore, Dr. Hart was one of its deputies from the diocese of Connecticut, and also a member of the Committee on the Standard Prayer Book. On the seventeenth day of the session he was chosen secretary of the House of Bishops, his predecessor, Dr. Tatlock, having resigned after a long and noble term of service. On the same day he was also appointed Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer. . .

“As it was my privilege to have a desk beside his own at every Convention in which he served the House of Bishops, I could not fail to become more and more impressed with the charm of his personality. It was always an inspiration to see how smoothly he and his work got on together, and to see how often his memory proved to be a kind of record file of the business of the House. . . I was thankful also for his sake and for my own cheer that one of his many graces was the fine sense of humour that sparkled from his lips now and then, and which doubtless served as a safety valve when his earnest energies were under high pressure.

“Dear Dean Hart! It is no wonder that bishops and Berkeley students were proud of him and loved him. It is no wonder that all who were fortunate enough to know him are cherishing his memory. The world is better because he has been in it but not of it. The Church is richer with the riches of his life that he has lived for it.”

As the Secretary thoroughly understood parliamentary procedure, it can be readily understood how much he facilitated the business of the House of Bishops by his instant adaptation to every variety of its action.

Not the least helpful perhaps of his services was the fact that every morning of the nine conventions of which he was secretary [24/25] when he took his place at his desk he had ready the minutes which he had written in full the night before.

The Right Reverend Thomas F. Davies, D. D., Bishop of Western Massachusetts, has recorded his impression of one of the recurrent incidents most frequently cited of Dr. Hart’s secretaryship:

“No one who has sat in the House of Deputies at the General Convention since 1892 is ever likely to forget the arrival of messages from the House of Bishops. The coming of one was a distinct event. The business of the House stopped while Dr. Hart walked up the passage and presented the message. His figure and walk became familiar, but there was always something in his bearing that added dignity to the incident. His whole presence denoted the ecclesiastic, for he was of a distinctly priestly type. The Oxford cap in his hand, to me, always symbolized the scholar, the man of solid and accurate learning. A look at his face and expression might well have made a bystander exclaim: ‘There goes a man of thoroughly upright and righteous life!’ Several deputies have said to me: ‘It is worth coming to the General Convention just to see Dr. Hart bring in a message!’ If the House of Deputies ever failed to attach due weight to messages from the Bishops, it was not because of the way in which those messages were delivered.”

Dr. Slattery has also quoted the Secretary of the Upper House when he looked into the garish hall called Moolah Temple in St. Louis. “Instantly came the short chuckle from Dr. Hart, as he said, ‘Give thy servant two mules’ burden of earth, when my master goeth into the House of Rimmon!’ ” Students of “Piety” at Trinity recall that Professor Hart explained that the diplomatic oriental wanted some sacred Jewish ground to stand on in the heathen temple.

Once at that same Convention when the strain became a little tense, the Secretary left everything behind, went down to the wharves by the river, and sitting there on the dusty timbers by the mighty “Mother of Waters,” said the Te Deum.

The Secretary of the House of Bishops was also, not by virtue of his office, but of himself, Registrar of the Church and Historiographer of the Church. The results of those labors rest in the archives of the General Convention.

Life at the Berkeley

Sacred studies and great offices of the Church seem naturally associated with Dean Hart’s residence in Berkeley. More immediate than the offices were the class room lectures and the daily Services in Chapel.

Even in a Divinity School students sometimes have to be called to order.

An example of the gentleness of his discipline comes from the Berkeley. Some of the men on an upper floor were waxing rather noisy, and finally he went upstairs and spoke quite earnestly of the need of greater quiet, but with no reproof. At Evening Prayer of the same day when one of the students approached him, Dr. Hart said, “I hope I was not too severe this afternoon.”

All the wealth of his learning, his deep piety, and his personal friendship, was behind the simple phrase he used so often,

“Good night, and don’t forget to say your prayers.”

There are four pictures of Dr. Hart which we may visualize, to integrate in a unity his fulfillment of the office of Dean of the Berkeley Divinity School:–on the grounds, in his study, in the class room, and in the chapel.

There is a snapshot (above) which records the first. Dean Hart is coming along the walk in the rear of Jarvis House and the Wing. We imagine the great trees overhead, Williams Library across the lawn, the tennis court yonder, with the Church and Parish House of the Holy Trinity rising above, and the rear of St. Luke’s Chapel, its sacristy, directly in the line of his vision. He is garbed in his academic robes, the scholastic gown blown by the summer breeze, on his head the Oxford cap, its tassel blowing in the wind. He is smiling with the happy, friendly smile his boys knew so well–smiling at the photographer who has “caught” the Dean, and including in the smile the other students who are looking on and enjoying the scene. And he is doubtless responding with some laughing phrase, as he so often did.

Perhaps he never was more perfectly in loco than in his study. At night it appeared rather dimly lighted with the gas jets overhead. It would have seemed to try one’s eyes, but not his. They were not tired as in the daytime he sat facing the light, looking toward all the windows. His books surrounded him, at the right his large collection of Juvenal, with the Horaces and Virgils, from his days at Trinity College, with astronomies and mathematics, his Greek and his Hebrew, the sets of Church histories and of theology, and perhaps most characteristic of all, his large liturgical collections, interspersed with dictionaries, odd volumes, antiquities, and works of reference. He knew his books. He said once that he believed he had at least had every book in his hands, and looked through it, to see what was in it. On the lowest shelf of the bookcase behind him was the row of great antique tomes which Bishop Williams had placed there, which remain, and seem yet the backbone of the Apostolic and Anglican traditions of Berkeley. As he sat there talking and laughing he seemed to be able to do everything at once. His desk was always in perfect order, and he would be writing letters,–an occupation which with most people seems to be associated with preoccupation. But he would look up and say something, and his visitor would be encouraged to ask some question. Sometimes it would seem too remote for an answer to be expected, but the Dean would go on chatting, and presently the reply would come, drawn from the pigeonhole of his deep memory. No printed page seemed too dry to furnish some interest, and even merriment. The writer recalls an evening when he was looking through some Convention Journals. One by one he ran through the pages, reading a passage, noting some fact, and frequently laughing at something, the serious worth of which he valued, but which suggested something innocently amusing–a twofold attitude which ran so constantly through all his life. Thus, writing, quoting, talking, reading, the evening passed so that the memory of it was of learning, illumination, and happiness.

The writer never had the privilege of attending one of his [27/28] classroom lectures at Berkeley, but he sat at Professor Hart’s feet on Monday mornings during his college course at Trinity, in the recitations we called “piety”–for the first recitation Monday morning was on some religious topic. They were entirely serious. I do not know what the manner was at Berkeley, but in these religious hours of combined catechizing and lecturing at Trinity, the happy merriment of the companionable discourse in the study was dropped. We traced our way through the grave and serious course of the topic, on the Scriptures, or some Church history or doctrine, with the sense that our attention must be entirely given to the momentous subject in hand. It was not heavy or dry. The same ease of mental touch was present there as at other times. But it was very serious, very reverent, the importance of the theme was constantly kept in mind, yet there was a human tenderness, a sense of the gentle sanctity of life, which prevailed in all. With this, illuminating it, were also the frequent citations and illustrative remarks, which were so characteristic of all of Dr. Hart’s conversation and teaching.

All his students probably best love to think of him in chapel, both at Trinity and Berkeley. The service was always good. The singing of the hymns and the chanting was without doubt in conscious line with the academic tradition of England–a dignified men’s service–echoing the spirit of the long line of English Youth who have met for prayers before and after their studies from the time of the venerable Bede. There is no other tone exactly like that in the world. It is more personal than the monastic monotone of Rome, yet not so personal but that it is blended and subdued under the spell of the historic dignity of the Church, and the imposing consciousness of the Divine Presence. Dean Hart knew all that–doubtless he carried within the accumulated consciousness of all that reverent and revered past. He did not speak of it in that light. But those who worshipped with him undoubtedly felt, though not distinctly conscious of it, that they were in the unbroken line of those English students whose search after knowledge has ever been sanctified by Godliness. The supreme example at Berkeley was probably when at early Communion on Ordination Day he used Bishop Seabury’s chalice and paten on the altar.

Perhaps in this sketch of personal recollections of Dr. Hart as Dean of the Berkeley Divinity School, we may, in closing, descend from this solemn height to be his guest at the reception in the Jarvis House. The House was left as in Bishop Williams’s day as nearly as was possible. Dean Hart was the ideal host in an academic institution. He could not exactly be called “a gentleman of the old school,” for his social grace was more easy than that which is naturally associated with that term. But he was fond of good silver and handsome china and plenty of it. Nor was he unmindful of the physical needs of mature men and women who had come from a long Ordination Service, or of the taste of young men and women for good things to eat. He served an abundant luncheon, and served it handsomely. Through the crowded rooms he constantly moved, with his smile and laugh and words of welcome adding to the general happiness. There was never any levity. His presence instinctively made it impossible. But it was an occasion of good cheer. And when at the end of it his friends bade him good-bye, it was with a happy memory, and with the happy anticipation of one more such occasion when June and Ordination should come again.

When one thinks of the activities of Dean Hart the impression is that his nature was a pluralism. As one considers his religious life there is no doubt it was a unity. The college life was in itself a unity. So was the Berkeley life. So in a true sense was the General Convention life. But there were other fields which are extremely difficult to co-ordinate. All were really held together by the central religious life. In themselves they appear separate, so let us think of some in that way.

Incidents of Travel

Dr. Hart was in general a good traveller, though it is not probable that he liked long journeys. But ordinarily he never seemed to come back tired. His friends observed that a little went a long way. A run up to the White Mountains for a week or two, or to Saratoga for the convention of a learned association, sufficed.

He usually started alone, but did not always continue so. Two or three incidents will show how he made friends as he travelled.

Once he was waiting at a station on the Valley Road, and reading a story, naturally a good one. Looking up he saw a newsboy reading a lurid dime novel. After a time he asked, “Wouldn’t you like to exchange for a while? I would like to see your book.” The boy in stunned silence complied, and after some time Dr. Hart returned it. On the train the conductor said, “Now, Dr. Hart, why did you do that?” “Well, I really did want to see his book, and I thought it wouldn’t do him any hurt to read something else for a while.”

The following incident noted by a bystander is probably but one of a thousand of a like character unrecorded:

“As he was going to the railroad station one day a freight train was on a siding. Just as Dr. Hart was passing a grimy-faced engineer was crawling from beneath the puffing engine.

“‘Good morning!’ called the dean, in a voice so full of the joy of life and of seeing people that it was plainly heard above the panting of the engine. The prostrate man looked up, at the sound of the happy note, and met the other’s smiling eyes. His mouth widened into a friendly grin and he waved his wrench with his coal-blackened hand.”

The best-known story of local travel is that of the trolley car which was stalled about midnight at Cromwell in a snowstorm. It was told at considerable length in the newspapers, but must be condensed here. The car left City Hall, Hartford, at 9:15 in the evening. It rocked along Franklin Ave., was delayed by drifting snow and snow plows, struggled on to Rocky Hill, which it left some time after midnight, “and headed for the fatal plains of North Cromwell. . . The car started. Then the rear truck went off the rails. No telephone near, and the thermometer down to zero.”

There was a varied company on board, some of whom began to drink. This was stopped by the conductor. Then some man in his impatience began to swear. Dr. Hart intervened, saying, “It seems to me we can use the time better than by swearing,” and began a humorous account of his sixteen hours’ ride on the “New Haven” under similar circumstances. His good temper was contagious. Others had like tales, and they all passed the time cheerily, till the car drew up at the Middletown post-office, four hours from City Hall.

Hospital Ministrations

Dr. Hart’s ministration in the Hartford Hospital would make a book, if they could be recorded. Who can imagine the number whom he comforted? For during forty years he visited the hospital Sunday afternoons, reading prayers, making short addresses, going from ward to ward and administering the Holy Communion, and ministering individually at bedsides. The influence of that constant celebrating of the Sacrament cannot be estimated. One or two instances of the adaptation of his ministry to various needs indicate much.

At one time he was speaking with a Roman Catholic woman, who was in great distress of mind, realizing that she would die, and anticipating the pains of Purgatory. Dr. Hart said afterward, in effect:

“I did not argue with her, for I thought in a very little while she would know better, but said the prayers, and left her to rest.”

At another time he ministered to a patient who was a bundle of nerves, and perhaps of temper, who was a sore trial to doctors and nurses. Finally Dr. Hart said to her, “If you feel that you need me, telephone to the College, and I will come at any time of day or night.” One morning she said, “Last night it seemed to me that I couldn’t stand the pain any longer, and made up my mind to telephone to Dr. Hart. Then I thought, such a good man deserves to be allowed the rest he needs, and I won’t disturb him.” The doctor remarked, “If Dr. Hart can quiet a case like that, his ministrations must be of some use.”

At another time a Jewish rabbi was in the Hospital, and Dr. Hart said for him some prayers in the Hebrew tongue. The rabbi died, but the action must have made a very deep impression, for when Dr. Hart died some time afterward, the rabbi’s widow sent flowers to his funeral as a token of appreciation.

His loving ministrations were extended to the little children in the Hospital and appreciated by them. The illustration showing him as he so often stood among them was used on a leaflet that asked for gifts for “A Free Cot for a Child.”

The Secretary of the Hartford Branch of the Guild of St. Barnabas, for nurses, wrote:

“He had, for many years, done the work of a Chaplain in the Hartford Hospital when, early in 1892, the work of this Guild for nurses was brought to his notice, and on the 15th of March of that year he organized the Hartford Branch. From that time he was unwearying in his services for it, never missing a meeting unless more important duties intervened, and none who had the privilege of listening to his words of counsel and help can forget them. Deeply spiritual as they were and setting forth the teachings of the Church, in its yearly round, they were at the same time eminently practical, pointing out where the help and strength were to be found in which to live the daily round and do the common task.

“His further generous gift of time in carrying on the business meetings and joining in the social side of the Guild, with his genial good will and ready interest, made each member know and feel him as a friend, and one to go to in special times of need. Many of the members will say what one nurse has written, ‘Dr. Hart’s death is a great sorrow to all of us who belong to the Guild, and to me it is a great grief and a feeling that I have lost a personal friend.’

“May we all strive to live as he has taught us by his example and word.”

From the Middlesex Hospital came this story:

A young man was lying in a bed in one of the wards, very ill and weak. Dr. Hart coming in saw him, and went to him, laying his hand on his head, and saying some comforting words. Then he knelt and said some prayers. After he went out, the patient asked, “Who is that man?” The nurse told him, and he said, “No one has ever done such a thing for me before.

Hart and His New England

Dr. Slattery wrote Dr. Hart’s sister on the occasion of his election as Bishop-Coadjutor of Massachusetts, “I am glad you think it would be a pleasure to your brother to have me in his New England.”

With that authority we need not hesitate to call it Dr. Hart’s New England.

It was almost mystifying to see how one who was so loyal a Churchman could also be so thorough a New Englander.

It was natural that he should be proud of the history of Saybrook, colonized in 1635, two years after Winds——–or, but a year before Hartford, and three years before New Haven. Its picturesque details, the only New England colony founded by noble patrons, the fort built by Lyon Gardiner, its command by Col. George Fenwick, the pathetic story of Lady Alice Boteler, Col. Fenwick’s wife, the first site of Yale College,–these and other historic facts were of deep interest to the great grandson of “Priest Hart.”

The history of New England must have been to him a living drama, whose unfolding acted itself before his mind’s eye. Could we have had from him a complete course of lectures in that field, none would have been better balanced or more orderly progressive. A vivid element would have been the delineation of individual men, of whom he had real knowledge.

We had no such course. He did on many occasions give monographs on particular events and persons. When local anniversaries occurred he was frequently invited to speak, and then his familiarity with the details in point were an indication of his general knowledge.

Such events were treated with the utmost dignity, yet amusement rippled along the surface.

He greatly enjoyed the “dignifying” of the pews in the old Congregational meetinghouses, and the local customs were of great interest whether “lection cake” or the Governor’s cocade, and the picture was continuous in his knowledge, from John Eliot’s Indian Bible to Dr. Trumbull who was “the only man living who could read it.”

It is a pity that such a mind could not have been communicated to all who live within our borders, holding loyally to the Apostolic Church of the Anglican Reformation, together with love of old New England, yet welcoming into its large minded charity all who came afterward, the African Methodists, the Italian or Irish Roman Catholic, or the Jewish Rabbi.

It was, as Dr. Slattery wrote, “his New England,” for he possessed it in his knowledge and in his charity.

The Old Saybrook Home

In 1786 “Priest” Hart gave to one of his daughters “the tract of land called Pennywise.” In 1840 Dr. Hart’s father’s widowed mother built on that land situated in the midst of the village the home to which Henry Hart brought his youthful bride. Here Samuel Hart was born and grew up as a child and a lad. That home still stands and is located on the Old Post Road between the Acton Library and Goodwin Elementary School.

All his life he loved it, and came back to it frequently, often going into the garden, picking some peas and beans, perhaps, or pears, but especially flowers.

One of the most beautiful customs of his life was that, when he made his weekly visits home in the later years of his mother’s life, when she was confined to the house, in the fruitful seasons he invariably brought to her some tribute from the garden.

The “Hartford Globe,” under the title, “Dean Hart’s Corn Crop is the Best,” one summer day printed an article, saying,

“Who’s got the best looking field of green corn in Old Saybrook? Well, now, it will probably surprise some people to learn that it isn’t one of the natives, nor one of the persons who raises garden truck.

“It isn’t a farmer at all, but Dean Samuel Hart, of the Berkeley Divinity School, Middletown, who goes there every week for a visit at the home of his mother,” after many words of praise and an anecdote related elsewhere, the article concluded,

“And so it goes. Chickens and children and conductors and carmen all take to Dr. Hart. And now it seems to be the corn, growing with all its might and main in his garden just as though it, too, wanted to please him. Some folks have a way of drawing what is best in people to the surface.”

Summer mornings in his vacations, sitting on the piazza of the old home at Saybrook, he read the whole of Smith’s Bible Dictionary, unabridged, in four large octavo volumes, double columns, fine print, from Aaron to Zuzim.

Once a friend was talking to him about some common acquaintance, with whom he was not pleased. Waxing more and more indignant, he pointed to the hitching post in front of the old Saybrook home, and exclaimed, “Why, there isn’t any more of the milk of human kindness in him than there is in that post!”

“How do you know there isn’t any milk in that post?” flashed back Dr. Hart who would never allow but that in any human soul there was some milk of human kindness.

Varied Services

Members of the New York Alumni Association of the Berkeley Divinity School will always remember the Dean’s presence at those meetings. He always reported the condition of the School as carefully as if we were a commission in charge of its welfare, never with undue optimism, yet never with a word of apology, and never without some gleam of humor. For fifteen years he came to every meeting, in January, appointed at his suggestion, on the available day nearest the date of Bishop Berkeley’s death.

On one occasion he accepted an invitation to address the New York Churchman’s Association on the proposals for the further revision of the Prayer Book. It was characterized by his loyalty to the existing forms. He objected to the substitution of metrical hymns for the canticles. Yet he favored some condensation, as proceeding at once from the Te Deum to the Communion, and enrichment, in the provision of additional Epistles and Gospels. He noted that churches no longer used the Psalms for the first seven mornings of the month, as on the First Sunday the Communion was celebrated without Morning Prayer. It was in the midst of the war, and he said that a visiting English clergyman had recently told him that all objections to the use of the imprecatory Psalms had been withdrawn.

For thirty-four years also he went one Sunday in the month to Grace Church, Newington, of which the Rev. Jared Starr, in Deacon’s orders, was in charge, to administer the Holy Communion. At his death a minute of appreciation was placed on record, signed by all the officers and communicants of the parish.

Perhaps the very last thing that might have been expected of this dignified scholar and ecclesiastic was the summer’s visit to Marlborough, to the boys’ camp of the Good Will Club of Hartford, at the homestead of Miss Mary Hall, its superintendent. He rode out there in the old stage drawn by an amiable white horse, and a photograph shows him seated in breezy out-of-door garb on a stone wall, before a large American flag, smiling the good will appropriate to the name of the club.

Dean Colladay has said of his association with the Church Missions Publishing Co.:

“He became the first Vice-President, the Presiding Bishop being ex-officio President, and continued in that office until his death. He never missed a meeting of the board; and for many years he personally revised the manuscript of every publication that was issued. At all times his deep and unflagging interest, his broad and thorough knowledge of the Church’s missionary work, his wise counsels, and his unfailing courtesy, made his presence in the Company a tower of strength on which the other members gratefully leaned.”

His Last Days

Until his fatal illness of four days it is not recalled by anyone that Samuel Hart ever spent a day in bed. At Trinity College he had an attack of inflammatory rheumatism, but held his classes in his room, with his foot propped up in a chair. His whole physical organism was in effective working order all his life.

At the time of his death Professor Ladd wrote that for two years previously those near him had noted signs of decreasing vigor.

On Monday and Tuesday following Quinquagesima Sunday he had unusual shortness of breath, and on Wednesday, while sitting at his desk, he was attacked by a slight cerebral hemorrhage. Dr. Calef and certain Hartford specialists were summoned, says Dean Ladd, and “from Wednesday until Sunday morning the doctors and nurses, his sister, Mrs. Bailey, and groups of students two at a time day and night attended faithfully and lovingly unto him.”

He asked one of the nurses, “Will this sickness last long? Shall I trouble you long?” She answered, “No, Dr. Hart, not long,” and after that he said no more about his condition.

The ringing of the chapel bell had been discontinued, lest it disturb him, but at his request it was resumed.

There was some delirium, and he began talking to his sister Elizabeth in Latin. She said, “I don’t understand you, Samuel. You know I have not studied Latin as you have.” He replied, “That is so. It is a pity your education was neglected.”

Saturday morning Bishop Acheson came to read the prayers with him, Dean Hart saying that he would wait for the Communion until Sunday. At the close of the prayers Dr. Hart looked up to Bishop Acheson with an expression of great sweetness and gratitude.

Almost the first remembered words of the little Samuel were those with which he used to close the Church services he was trying to render, “Amongst and remainst.” Dean Ladd gives the story of his final benediction:

“On Saturday night when I was summoned again to his bedside it was known that the Dean was near his end. He was delirious, and thought himself conducting a Church service and preaching. At a pause in his sermon I spoke to him. He recognized me and shook my hand. I said it was a privilege to be allowed to see him. His answer was, joking, ‘I am not much to see.’ When I stepped back he charged the nurses to show me the way out. This bit of courtesy was his last conscious act. It was just past midnight. Fifteen minutes afterwards I knelt at the death bed with the nurses, two students [Loyal Y. Graham, 3d, and Harold C. Mills, the first American Divinity student killed in the war], and his sister, and said the commendatory prayer. In the last moments he had thought himself once more in church, and his last earthly words were, The Lord bless you all!'”

Bishop Acheson sent notice of the funeral services, giving the titles which have been recognized as perfectly descriptive.

On Wednesday, February 28th, the coffin was brought into St. Luke’s Chapel, lights set at the head and foot, and at 7 o’clock the Eucharist was celebrated by the Suffragan Bishop, assisted by Professor Ladd.

At noon the Rev. Dr. Lucius Waterman said the full Litany, with the Commendatory Prayer.

While the chapel bell tolled the body was borne to the Church of the Holy Trinity.

In the first procession were:

The Faculty of the Berkeley Divinity School.

The Students of the School.

The Beta Beta of Psi Upsilon, Trinity College.

The Xi Men of Psi Upsilon, Wesleyan University.

The Faculty and Trustees of Trinity College.

The Faculty and Trustees of Wesleyan University.

Representatives of —

Yale University.

The Theological School of Hartford.

The Ridgefield School.

The Conversational School, Middletown.

The Pastors of the Middletown Churches.

Phi Beta Kappa.

The Middlesex Hospital.

The Hartford Hospital.

The Connecticut Historical Society.

The Middlesex County Historical Society.

St. Barnabas Guild for Nurses, Hartford Chapter.

The Humane Society.

The Open Hearth Mission, Hartford.

The Good Will Club of Hartford.

The Wadsworth Athenaeum.

Former Governor of Connecticut, Simeon E. Baldwin, and other notable citizens of the State were present.

In the second procession were:

Some two hundred and fifty of the Clergy.

The Rector of the Church of the Holy Trinity.

The Members of the Standing Committee.

The Bishop of Western Massachusetts.

The Suffragan Bishop of Connecticut.

The Bishop of Connecticut.

The Sentences were said by the Rev. Storrs O. Seymour, D. D., President of the Standing Committee.

The Psalms were sung by the choir of forty voices, conducted by the organist, Mr. William B. Davis, Bac. Mus.

The Lesson was read by the Bishop of Western Massachusetts. The Hymn, “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah,” was sung by the choir and congregation.

The Creed and Prayers were said by the Rev. George T. Linsley, Rector of the Church of the Good Shepherd.

The Benediction was given by the Bishop of Connecticut. The interment was in the ancient burying ground of Old Saybrook.

The Committal was read by Bishop Brewster, standing at the head of the grave, the Prayers by Bishop Acheson at the foot, and earth was cast upon the body by Dr. Seymour.

A choir of students sang “Rock of Ages,” and Bishop Brewster pronounced the final Benediction.

On the tombstone is the Transfiguration text suggested by Dr. Slattery,

THINE EYES SHALL SEE THE KING IN HIS BEAUTY.

A Prayer by Doctor Hart

Make us, we beseech thee, O Lord our God, with watchfulness and care to await the Advent of thy Son Christ our Lord; that whensoever he shall come he may find us not asleep in carelessness or sin, but awake and rejoicing in his praises, who liveth and reigneth with thee and the Holy Ghost for ever and ever. Amen.

Samuel Hart

1845–Wednesday, June 4, born at Old Saybrook, Conn.

1845–October 19, baptized in Grace Church, Old Saybrook, by the Rev. Alpheus Geer.

1860–June 7, confirmed in Grace Church, Old Saybrook, by the Right Reverend John Williams, D. D.

1862–Entered Trinity College.

1865–Phi Beta Kappa.

1866–Graduated, Bachelor of Arts, Optimus.

1868–Tutor in Mathematics, Trinity College.

1869–Master of Arts, Trinity College.

–June 2, Deacon, Bishop Williams, Church of the Holy Trinity, Middletown.

1870–June 28, Priest, Bishop Williams, Christ Church, Hartford.–Tutor in Greek, Trinity College.

1873–Professor of Mathematics, Trinity College.

1874–Registrar of the Diocese of Connecticut.

1878-9–Leave of absence, in British Isles, in charge of Church of the Holy Trinity, Paris.

1883–Professor of Latin, Trinity College.

1885–Doctor of Divinity, Trinity College.

1886–Deputy to the General Convention.

— Member of Commission on the Revision of the Prayer Book.

— Delegate to Scotland, Seabury Centennial.

1892–Secretary of the House of Bishops.

–Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer.

1898–Registrar of the General Convention.

–Historiographer of the Church.

1899–Sub-Dean of the Berkeley Divinity School and Professor of Doctrinal Theology and the Prayer Book.

— Doctor of Canon Law, Trinity College.

1902–Doctor of Divinity, Yale University.

1908–Dean of the Berkeley Divinity School.

1909–Doctor of Laws, Wesleyan University.

1914–Bohlen Lecturer, Philadelphia.

1916–Paddock Lecturer, General Theological Seminary.

1917–January 25th, Sunday morning, entered into rest.

Editor and Author

Satires of Juvenal, 1873.

Satires of Persius, 1875.

Scipio’s Dream (Cicero), 1887.

Bishop Seabury’s Communion Office, with notes, 1874.

The Mosarabic Liturgy, 1877.

Address, in Report of Seabury Centenary (which was probably compiled by Dr. Hart),

1885.

A small volume entitled, Four Sermons on The Transfiguration of Christ, 1890.

Maclear’s Instruction for Confirmation and Holy Communion, 1895.

History of American Prayer Book in Frere’s Proctor, 1901 (also in type for the blind).

Short Daily Prayers for Families, 1902.

History of American Book of Common Prayer, 1910.

Faith and the Faith (Bohlen Lectures, 1914).